Shipwreck Off the Coast of Alaska

Interest

In the decades following the tragedy of the La Pérouse expedition, Lituya Bay drew the interest of American scientists and anthropologists.

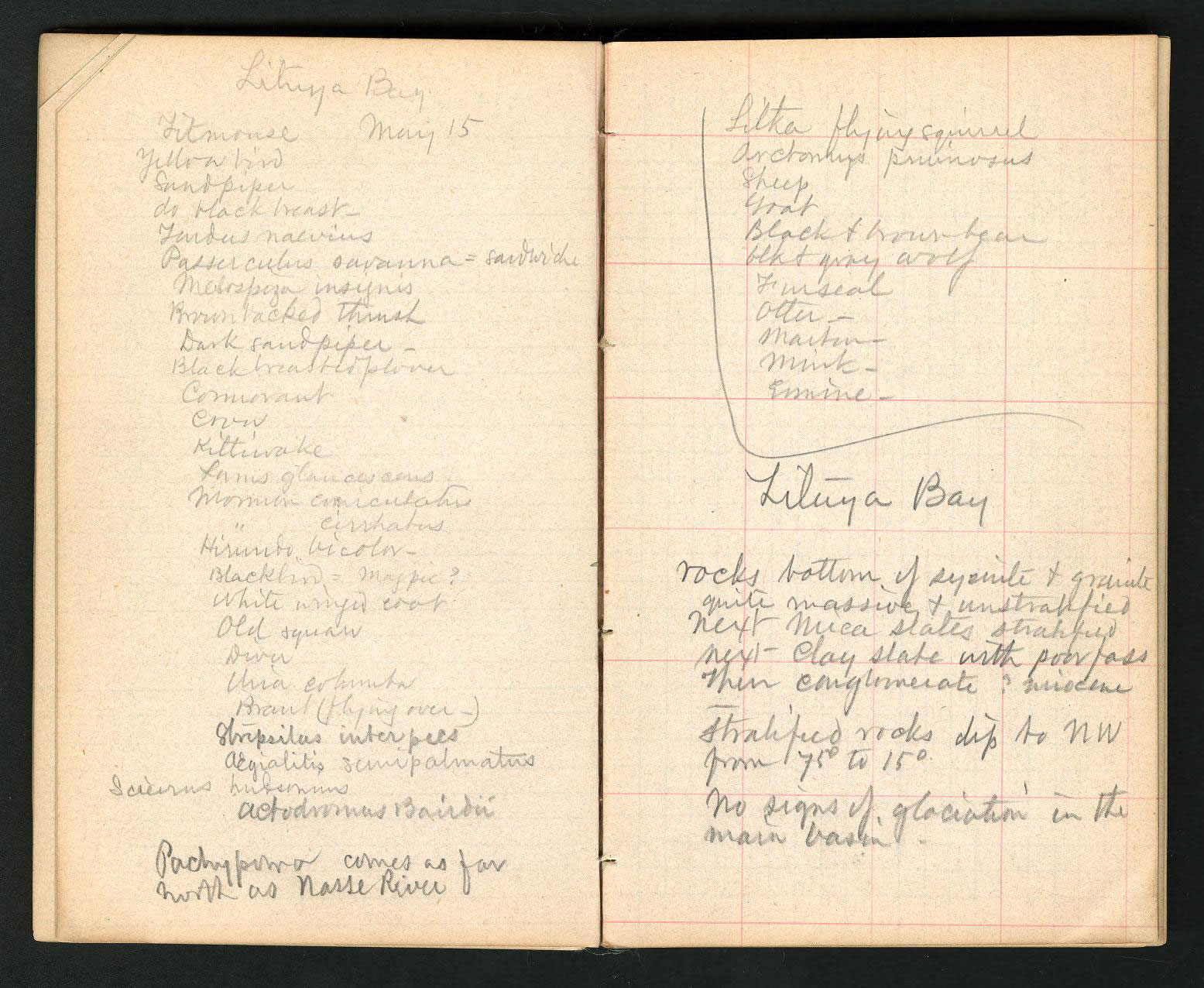

Dall’s 1874 field notes from Lituya Bay, listing the species of animals, types of rock, and glacial features he observed while there. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Courtesy of Biodiversity Heritage Library.

In 1874, prominent naturalist William H. Dall entered the bay to record the area’s wildlife and geologic features as part of an expedition for the US Coast Guard Survey. Almost a century after La Pérouse, Dall described in his diary the hazard of the bay’s mouth, writing, “the bar across the entrance is a raised spit ten or twelve feet high with numerous rocks off the end—the water on the other [ocean] side is much more bold. The entrance is very narrow, not more than wide enough for one vessel to enter at a time.”

The La Pérouse expedition had left a memorial for their fallen sailors on a landmass they had dubbed Observatory Island but renamed Cenotaph Island after the accident. When Dall visited Lituya bay, he looked for the memorial without success, writing, “I [took] the boat and went up the bay, circumnavigating the island. Found no trace of monument or observatory.”

The pipe G.T. Emmons collected from Lituya Bay, now in the National Museum of the American Indian, New York. Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian.

In 1886, George T. Emmons, an ethnographer and Lieutenant in the American Navy, met with members of the Tlingit people living in Lituya Bay. While there, he traded for this pipe, which symbolically represents the dangerous unpredictability of the bay’s tide: “At one end is shown a frog-like figure with the eyes of haliotis shell, which represents the Spirit of Lituya, at the other end the bear slave sitting up on its haunches. Between them they hold the entrance of the bay, and the two brass-covered ridges are the tidal waves they have raised, underneath which, cut out of brass, is a canoe that has been engulfed.”

Independent from the written European account of the expedition, the story of La Pérouse’s arrival and two dinghies sinking remained a Tlingit oral tradition for at least a century. According to Emmons’ account, he met with the chief of the Auk qwan tribe, who recalled his ancestors’ shock at first seeing the two French ships sail into Lituya Bay, which they originally mistook for the wings of the spirit raven, Yehlh. According to tradition, to look at Yehlh would turn one to stone, so the tribe sent a nearly blind man to first meet the visitors on their ship. When he returned safely with some food, they lost their fear and went on to trade further with the French explorers, who suffered the disastrous shipwreck a couple of weeks later.